Every instructor has a particular skillset that they pay special attention to; be it the mechanical fundamentals, precision accuracy at distance or more dynamic skills such as speed shooting. This doesn’t mean that other important skills are ignored, far from it. Rather (at least in my case) it makes the focus more evident in that the total instruction leads back to the foundation of that particular skill.Â

For me, everything (after the basics are understood) begins with close quarters shooting. Not static, not ideal, a few feet of violence where life is usually at its greatest risk and reaction time is usually at its least. Accuracy at distance is important to master, the greater the distance from a target the more exaggerated any mistakes or improper techniques will be, but in close distance reaction time must be at its shortest and technique fluid and precise to provide the advantage.

It’s been said more than once that if you can do it at 25 yards; you can do it at 2 yards. I’ve always disagreed with the statement because it doesn’t factor in a lack of time, close proximity to the threat and the physical threat of being close to, if not in arms reach.  Skills must have a high economy of movement; many possible variables that are not issues at distance must be considered and practiced for. Distance is a luxury. It may make accuracy more difficult, but it gives options.

It’s also been said that “slow is smooth and smooth is fast.” This may make someone think that slow=fast. It doesn’t. Slow, repetitious movement is where speed begins, where we form the so-called “muscle memory” (Hebbian Plasticity) of a technique. With all things focused on reality, speed is both the shortest period of time a motion can be performed and that motion performed with the highest degree of mechanical efficiency.

Why Close Quarters?

A lack of distance means a lack of time to react, reduced choices and in most cases a more acute disadvantage when reacting to a threat. Common sense tells me that in a vast majority of self-defense shootings, most prominently those outside of the home, will occur in conversation distance. If someone is in an argument, or a threat approaches you to perform a robbery or an assault, they will be consistently close. If the attack or threat is with a handheld weapon, their effective range (and effectiveness of the threat) is limited by the length of that weapon (be it bat, knife, club, stick etc.) plus their physical reach and speed at which they can close any gap. Even when armed with a firearm, the threat must be within ear shot to affect any sort of conditional profit crime (demanding wallet, keys, car, bag, etc.) and would normally do so at a distance where their threats could not be over heard, drawing the attention of potential witnesses.

There is no “bright line” distance here. It can be 2 feet, 4 feet, 6 feet or an even greater distance but it’s safe to say that very few crimes of profit take place from 10 or 15 yards. Any time I am given the opportunity to speak with a felon convicted of a physical robbery in a LEO capacity, I ask them how close they would get to their victims. For those who bother to answer (instead of telling me to do something that is anatomically impossible), the overwhelming answer is with arms reach. Their reasoning for this follows common sense. They want to be close enough to keep their speech as low as possible and close enough to be physically threatening, while also being close enough to get that which they are demanding in a robbery or to escalate an altercation with physical violence. Not all situations you may find yourself in will be within the common “close quarters” distance, but I will risk saying based on my experience that you are far more likely to defend your life in close distances than more (relatively) comfortable distances.

With this in mind, is it more important to spend a majority of your time working towards greater distance accuracy or building speed and precision at closer ranges? All things considered, I personally train for the most likely to the most unlikely. As awesome as it is to shoot nice groups at 25 yards, I know that bad guys aren’t going to sit still long enough at that distance to give me time to shoot a pretty group and it’s more unlikely to encounter that bad guy at such a distance. Possible of course, which is why I practice for it but my practical and precision accuracy inside of five yards with an eye on being as fast and precise as possible from the method I carry is more important. Especially since my body is going to make fighting in close quarters more difficult.

Remember “if you can do it at 25, you can do it at arms distance?” This is plainly false as we are involving a totally different set of skills, removing the traditional luxury of time and fighting from very less-than-ideal conditions that don’t lend themselves to neat stances and conscious recoil mitigation or other factors that are considered at distance. Some people tend to confuse what happens on the range with what happens in real life. The mechanical fundamentals largely remain the same, but the physical mechanics are very different.

Reactions to a threat, Startle and otherwise.

Imagine leaving a grocery store in the evening, not quite dark but not light. Twilight. It’s busy, as grocery stores usually are in the late afternoon/early evening, so you are parked past those fortunate enough to get there before you. As you hunt your car down you see someone out of the corner of your eye cutting through the rows of parked cars headed in your general direction. Once you see them you move past them and all but forget they were there. You reach your car, toss a few bags in the trunk, shut the lid and open the driver’s door. That’s when you hear someone right behind you say “Hey†you turn on common habit and find someone within arm’s reach holding a knife low to their waist, pointed right at you. The close proximity, the unexpected visual and the obvious threat may induce a startle reaction.

A startle reaction (also referred to as a startle response or startle pattern) is a psychophysiological reaction to an unexpected visual and/or audible stimulus. This reaction is an evolutionary reaction to protect the body. Humans begin developing a startle reaction in infancy, a Moro Reflex1 that develops as we age and evolves into what is commonly known as a flinch, reflex or startle reaction.

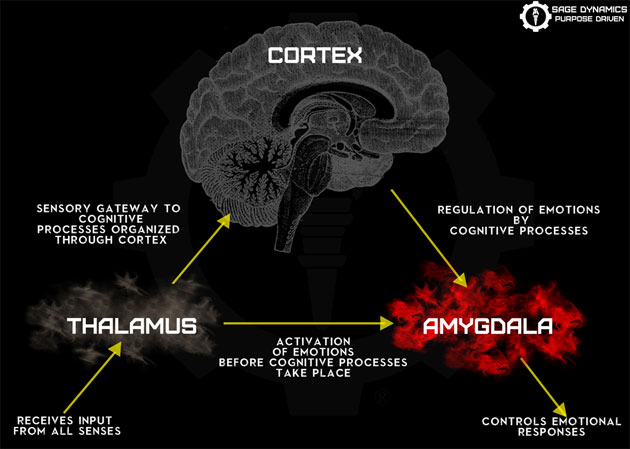

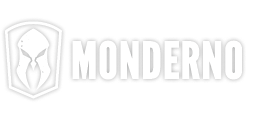

Controlled by the Sympathetic Nervous System, a Startle Reaction is a refectory reaction that does not require conscious thought and can occur in as little as 50 milliseconds, usually ending after 500 milliseconds2. When a threat (stimulus) is perceived, information is routed to the Thalamus in the brain, which will then distribute it to the appropriate cortex of the brain. In close quarters, this may result in a startle, in which case the information is directed to the amygdala, bypassing the “thinking†brain where OODA occurs3. The amygdala activates protective reflexes.

Here’s the rub: there is no standard startle reflex, despite some instruction in the firearms world to the contrary, as we humans have a wide choice of startle reflexes that our brain will choose for us and our training may or may not be able to replace what we do unconsciously. Furthermore, reactions vary greatly from visual to audible startles. There are at least 30 possible unique startle reactions4 in the untrained individual and these reactions can be very situation-dependent.

Okay, so when reacting to a sudden threat, which will primarily be a visual stimulus, what will your reaction be? Let’s go back to our example. Sudden audible clue, you turn and are confronted with a knife. Arms distance from your threat, what would an ideal reaction be? For me it’s a smooth sweep to my concealed weapon and as many rounds from the hip as needed to fight to full presentation.

A second option would be to attempt to control the hand/arm holding the knife while working to a position of advantage at which time the gun can be brought into play if needed. Both of these are trained reactions. The first is a reaction that functions in a number of varied situations, the second reaction requires physical contact with my threat and the number of possible variables increases exponentially. The answer lies in training for the “low road,” not the “high road” but we will get to that. First let’s look at what’s being taught out there right now.

A Conditioned Response is a repetitiously trained technique intended to replace or occur shortly after an initial reaction to a stimulus. The ideal conditioned response will replace a startle reaction, thereby shortening reaction time and increasing effectiveness. The draw/presentation is a conditioned response of sorts; we are given an audible (sometimes visual) cue on the range and then draw/raise our weapon and engage the target under a set of circumstances designed by the instructor. Because people are often shooting paper, the audible clue is what puts us into action, which goes against the idea of a conditioned response for a visual threat, yes?

Think of it like this; vision is our primary source of information on bad guys. If we can see them, our cue to go to the gun is most likely going to be visual, not audible. Their words or sounds that draw our attention to them may play a part but we will not use lethal force based on sound alone. Since the visual data we receive will decide what (if any) force is used, is there anything to be gained in training reactions that are based off of known audible startles? In two words: Absolutely Not. So why is it being done?

Enter the Landis-Hunt Crouch. I have seen more than a few variations of this crouch position in use for a few decades, and it is taught to varied degrees (depending on who is teaching it) to create a conditioned response to a threat, though the L-H Crouch doesn’t accurately address reality and attempts to remove common sense from the equation. The Landis-Hunt Crouch came about from a 1939 study by Landis and Hunt with the goal of recording facial expressions in startle reactions. The test subjects were seated and then exposed to audible startle noises such as bangs, crashes and gunshots from behind. Despite the obvious conclusion issues, this study gave us a Defacto body startle position and explanation. At least that’s how it evolved as it was picked up by martial arts trainers and firearms instructors over the years.

Startle in humans consists of the following set of muscle movements: blinking of the eyes, forward head movement, a characteristic facial expression that includes a widening of the mouth and occasional baring of teeth, raising and drawing forward of the shoulders, abduction of the upper arms, bending of the elbows, pronation of the lower arms, flexion of the fingers, forward movement of the trunk, contraction of the abdomen and bending of the knees.5

The obvious problem with this study is that it’s all about a reaction to an audible startle, sorry, a possible reaction. See, we didn’t evolve to where we are today based on one reaction for all situations, which would be foolish. Imagine throwing your hands up to protect your face when someone points a gun at you, or bending at the knees and extending your arms to your sides in reaction to a sudden obstacle in a running path. No, if we were programmed to react to each stimulus the same way we would long since be extinct. So why would someone teach one reaction? Remember “high road” and “low road” training? Let’s take a look at that to answer the question.

High Road pathway training is where the majority of training, particularly in firearms, takes place and it’s designed around how the brain functions when there is no startle. The High Road pathway is based on OODA and the lack of a reflexive startle: The stimulus is Observed, information is routed to the thalamus by our senses and Orientation begins as that information is routed to the appropriate cortex (most likely visual). The processed information is then downloaded to the amygdala and a reaction/response is generated in the form of a Decision and Action along with the generation of emotion and fear. From firearms to martial arts, High Road training is the common denominator in that it by implication or purpose designs reactions based on the relative luxury of time. It is creating reactions where unconscious actions may occur, but they are trained unconscious actions built to a level of competency by repetition. Hear a command, draw weapon, aim fire. Observe a thrown punch, move, block, strike back. These actions can occur very quickly but can’t approach the speeds of a startle.

The Low Road pathway is where very little training takes place, even if some disguise High Road training as such.   The Low Road is evolution cutting out the middle man (you) and generating a reaction based on what little information is present. The perceived stimulus is downloaded by the thalamus and then sent directly to the amygdala, which generates a protective startle. This is Observation to Action. The amygdala activates our Sympathetic Nervous System; a startle reaction takes place and only then is the stimulus information sent to the appropriate cortex where OODA processing will then occur.

Think of it like this; you are sitting at a baseball game with dugout seats. The pitch is thrown and the bat is swung, it breaks and the working end of it is propelled by chance and circumstance (and physics) right at your head. You are Facebooking so you look up right as the bat nears your head, your arms raise reflexively to keep the broken bat from hitting you in the face. No conscious decisions take place because there simply was not time. Had you been paying attention and seen the bat break at the moment it did and visually tracked it as it was propelled into the stands, a decision to block the bat or move your head could have been made based on time and continued visual input. What’s more, even if you startled needlessly, because the broken bat missed your head, or never reached your seat, you would still experience the emotions and fear that come with a startle.

Both processes, High and Low occur at the same time. Before that confuses anyone, let me explain. The amygdala is like an information processing center. It gets all the sensory data received by the body and is a critical part of the defensive pathways (High and Low) that exist in our built in programming. The pathways between the amygdala and the cortex are complicated. Those from the cortex to the amygdala are not as developed as those running in the other direction, which lets the amygdala exert its protective, reflexive will over us when there is no time to think. So while we may be trained to take the High Road in our reaction, the amygdala cuts in and forces a Low Road reaction in certain circumstances. The amygdala is primed for fear and emotion, once that occurs, it’s impossible in such a short period of time (literally milliseconds) to consciously take control over what is happening and use a preferred reaction. There isn’t always going to be a startle reaction; bad guys can be mere feet away and not cause one, especially if they were seen before they were perceived as a threat not as they were. High Road is important training, though Low Road is where we need the most advantage.

As always, context. What does this mean for close quarters shooting, or self-defense shooting in general? Reality is the ever-present issue when training firearms; as hard as some of us try to make range training and even Simunitons (force on force) training as realistic as possible, it lacks the objective fear and emotion that accompanies an actual use of force and we must include training artificialities for the sake of safety and training constraints.  We can get close, especially with force on force training, but we can’t get it as it occurs in real life.

So what options do we have? The brain has two paths to take when dealing with a threat, or danger; the High and the Low. They aren’t so much either/or choices as they are two roads to the same place. The nature of the stimulus decides which road is taken and in turn how much control we have over how our reaction. To train a startle reaction, it has to be understood that either road is driven by Rational or Experiential thinking.6 Rational thinking is cognitive processing without a great deal of emotional involvement.

Experiential thinking occurs under high stress and is far more efficient than Rational thinking when confronting perceived danger. Because Experiential thinking is more adapt at high stress, it is the common default when reacting to a threat. Our brain is hardwired to deal with emotion and fear, we have only (historically speaking) evolved to the point of a polite society, in other words we have spent more time dealing with danger than we have living without its every day presence. Experiential thinking governs our responses to threats, and it does so by drawing from our evolutionary experiences. Once a reaction process begins, it is nearly impossible for use to consciously control it until it runs its course, which means that training a startle reaction would require you to overcome the hardwired, deep structure programming.

We have already seen in the past that stress reactions easily overcome range training. In the Westmorland7 and later the Burroughs8 study, it was empirically shown that the Modified Weaver stance was not used in an overwhelming number of situations under real life stress, which (begrudgingly with some instructors) saw trainers get away from teaching it.  What this means is that years of training in a shooting stance was effectively rendered pointless by our brain. It took decades for Modified Weaver to be shown ineffective and almost as long for it to disappear from the training world (though it still pops up every now and then).

In order to effectively train a conditioned response for the Low Road, the technique has to be compatible with what the amygdala will direct the body to do in a startle reaction and it should be trained as realistically as possible. Remember how there are over thirty possible startle reactions, and they vary from audible to visual? This means that training for a startle reaction much be natural, accepting that High Road training cannot (rare exceptions permitted) override our very psychophysiological programming. We see this in martial arts; systems such as Pramek, SPEAR and Kelly McCann (to name a few) work from the natural reactions of the human body coupled with strict biomechanics. We don’t see it so much in firearms. We have lauded the OODA loop for years; it has been ingrained in thousands of shooters, entire training programs built around it and for good reason. But OODA is more High Road than Low and it doesn’t accurately address the startle reaction.

As already mentioned, some instructors teach automatic startle reactions in their courses and the problem with that from what I have seen is they pick one, usually the Landis-Hunt Crouch and it becomes a standard. This doesn’t provide much context to the student as each of them can review their own experiences and easily see that of all the times they have been startled in their life, it was different much more often than it was the same. But what about the LH-Crouch being a superior “natural†startle reaction and therefore it should be the default? No. It isn’t. Even if the amygdala could be programmed with High Road training, the arm behavior in an LH-Crouch makes very little sense outside of a thrown strike. The arms come up to protect the head, an ideal reaction for a thrown punch or even some attempted strikes with an edged weapon (if the weapon is even perceived). It makes very little sense when reacting to a threat outside of arms reach who is presenting a weapon and even less sense as distance increases and startle reactions are less likely. To put it bluntly, teaching a standard reaction is well meaning, but it’s snake oil and a disservice to the student. The solution to fighting through a startle reaction isn’t complex; you build off of what happens, not try to reprogram what happens.

Close quarters shooting is all about the lack of time, directing force as quickly as possible and making movement as soon as possible. If time is lacking, training someone to perform a reflexive startle reaction where there otherwise might not be one is taking valuable time away that could be better spent directing violence against the threat.  Off line movement training has become more common, which is of great benefit to students and self-defense shooting as a whole. What still lacks in some circles is more aggressive and focused close quarters shooting, which is where startle reaction methodologies must be instructed.

The startle is going to occur; instead of focusing on how to change it, I focus on what it triggers based on available information at the moment of conflict. Practicing a prepared arm stance is ideal, arms kept near the waist with hands in front of the abdomen, though this position is static in that it doesn’t account for daily life and general interactions with our environment. We simply can’t move around every hour of the day maintaining this position and the level of mental awareness that would accompany it.

Keeping that in mind, any interaction with an unknown individual or a potential threat should place the hands in this area for easy access to your weapon and shorten the distance to block an attack. It also positions the hands for offensive protective moves against edged weapons, blunt weapons and strikes. When startled, our visual information is processed and a reaction is formulated either directly by the amygdala (arm to block a swing or protect the head, stepping out of the way, ducking, flinching, blinking, reeling back etc.) or as the startle passes and OODA begins, by a trained (or untrained) reaction. The natural startle reaction, whatever it may be, can be honed and conditioned by confidence and conditioned reactions to threats, but should not ever be replaced by a reaction that only fits a small number of possibilities.  This means, above everything else that training and practice need to be as realistic as possible.

Close quarters shooting, training and practicing more realistically.

The development of more realistic training and practice methods is knowledge dependent. That goes for me just as much as it does the reader. The knowledge can be helped. Learning can be free, and often is. Lessons learned, collective knowledge and professional development between peers is the start, looking outside firearms to psychophysiological research of the human body under stress is the evolution, and I would venture to say much more beneficial.

Personal startle reactions to both visual and audible stimulus can be verified with the help of friends, or better, seek out a reality-based (actual, not just buzz word) Martial Arts and begin training the body. Knowing how you respond to a visual/audible startle (as opposed to letting someone tell you definitely how you WILL respond) lets you shape your personal practice and begin addressing the realities of close contact. Shooting inside of arms distance, working towards maximum chance for incapacitation in the shortest period of time (such as when “point shooting†from the hip, target the thoracic cavity or head instead of the traditional pelvis) and directing force to your threat to fill the dead space in the time it takes you to draw your weapon. Above all else, seek out a handful of instructors that have the experience and common sense to address the physical and the situational. You are more likely to have to use force at closer distances than further and there is always the possibility of having to defend against an edged or blunt object.

My personal methodology is simple; I closely work with Matt Powell of Pramek to bring reality based martial arts experience into firearms because I know that I don’t know everything. Matt’s approach to self-defense is well documented and a sort of realism that is refreshing. I also spend a great deal of time researching the subject from the medical standpoint. If new advances in understanding the human mind under stress happen, I want to know about it and incorporate it into training if it’s relevant. None of this would be as worth it if I didn’t spend nearly as much time testing and verifying techniques before I ever put them in a course of instruction.

Close quarters shooting, especially from the citizen and the LE’s point of view is all about reacting to a threat in the shortest amount of time possible. Knowing what your body can and will do in this situation is the best way to develop a personal plan and practice for any variable that’s within the realm of possibilities. Dedication to the art and skill of self-defense shooting starts with the fundamentals, from there it needs to be as realistic as possible and an ever present possibility is facing violence without the luxury of distance or time. Train accordingly.

Notes

1 Assessment of Primitive Reflexes in Newborns, M Sohn (2011)

2 Amygdala and Anterior Cingulate Cortex Activation During Affective Startle Modulation:a PET Study of Fear, Anna Pissiota (2003)

3 Differential Contribution of Amygdala and Hippocampus to Cued and Contextual Fear Conditioning, R. Phillips (1992) The Role of the Amygdala in Fear and Panic, Doug Holt (2008) The Role of the Amygdala in Fear and Anxiety, Michael Davis (1992)

4 Boo! Culture, Experience, and the Startle Reflex, Ronald Simmons (1996)

5 Neural Mechanisms of Startle Behavior, Robert Eaton (1984)

6 Conflict between intuitive and rational processing: When people behave against their better judgement, Seymour Epstein (1994) The relation of rational and experiential information processing styles to personality, basic beliefs, and the ratio-bias phenomenon, Seymour Epstein (1999)

7 Isosceles VS. Weaver Shooting Stances, Law and Order Volume:37Â Issue:10, Hal Westmorland (1989)

8 Bill Burroughs Shooting stance study (1997) Cited in Scientific and Testing Data Validating the Isosceles and Single Hand Point Shoot Techniques (1998) Bruce Siddle

Great stuff!

Great stuff… my recommendation is to remove the photos of the attacker with the knife in the photos. Or next time try not to post a pic of a guy defending a “palm grip” knife attack with technique proven not to work.Those are old world defense techniques that should no longer be used when defending a knife attacker. I mean that as constructive as possible… im not some asshole trying to knock what you have done here, the article is very interseting. But after training for years in knife defense the techniques shown, might get some of your followers (youngsters included) seriously hurt. Just a thought.

Since I’m referenced in the article. I don’t want to derail and make this an article, but I also look very closely when someone says what is being shown could get someone seriously hurt. Aaron through Sage and I through Pramek go to great lengths to make sure what we are teaching gives someone the best chance to go home, be they make a defense armed or unarmed.

There is a difference between empty hand knife defense and knife defense to the gun. I agree with you that technique is not preferable in empty hand situations, but this photo sequence is about going to the gun – which is different.

I’ve put student after student for about 6 years through this scenario in and out of protective gear, not told them what is in the attackers hands, and let them go. At this distance in a sudden attack the attackers movement is visually and neurologically processed and reacted to first, not the weapon. The weapon could be a knife, hammer, pipe, soda can. We have found a large majority of the time the student doesn’t know what weapon they are being attacked with until they move beyond the initial spontaneous contact and reaction, and have a split second to visually recognize the weapon in OODA.

As this is the case, in Pramek’s experience most people will put atleast one hand up to defend against a sagittal downward attack. The question is how do we weaponize that movement and subsequent movements to get to the gun.

That leads to the need for immediate deflection/block of the incoming blow. Knife defense and knife defense to the gun are two different things. Among a variety of defense to the gun methods, the photo sequence show ONE.

Is it the best, no.

Is yours best? No.

Nothing works best in reality – it either works or it doesn’t.

This movement is block/deflection/possible control with one hand available…which is what is needed to get to the gun, not to begin counter movements or strikes. It works.

Much respect

Matt

Ever watch a house cat stalk a mouse or even a cricket? The hoodlum who intends to carjack you while you’re filling the tank, or loading the groceries in the trunk moves the same way.. Being alert while doing something lets you detect and plan. Pilots look out of the windows in a planned manner of scanning, looking for certain things, primarily other airplanes, maybe flight instruments and landmarks on the ground such as rivers, highways and cities.

Pilots don’t like to be surprised by an unseen airplane passing close.

In the same way, the driver loading his car or topping the tank needs to stay alert, needs to look around by looking AT things, the shadows, the two man team stalking you, Any person within 15-25 yards is a potential threat. So look alert and take in details, where are they looking and what are they doing with their hands?

Fighter pilots quickly learn to check their 6. Fighter pilots have a wing-man, maybe they have AWACS. The potential crime victim needs to train their eye to see the threat before it gets close.

If you’re pumping gas and one or two people approach you, open the door or step around the car, get the pump between you and the threat.

If you’ve got friends or family with you, you have a protection load you must meet, but use them to your benefit. Teach your spouse to watch your back. Your spouse needs a carry license too. Teach your kids to be alert and to warn you calmly.

If you’re carrying concealed and need two hands to clear your garment and draw, don’t expect to also do hand to hand defending against a knife or club. It doesn’t mater how cold it is, open your coat when you get out of your car.

Try to look dangerous and maybe your appearance will prompt the mugger to look for an easier victim. If you’re 20-30 in good condition, your task looking like a tough nut to crack is easier than a senior citizen with a cane or walker. A cane is a weapon if you train how to use it as a thrusting tool and not a baseball bat swinging.